© Wellcome Collection. View of the relocated Crystal Palace exhibition with Richard Owen’s fantastical dinosaur reconstructions in the foreground, by the London printer George Baxter.

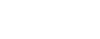

Since the first dinosaur bones were unearthed and identified by William Buckland in the 19th century, there has been a frenzy of research to better understand how these creatures lived and what they looked like. Technological progress means that we are constantly learning new things and advancing our understanding of dinosaurs. For example, the famous Crystal Palace dinosaurs – a series of life-sized statues built around a lake in the grounds of Crystal Palace Park – were groundbreaking when first built. They remain a popular attraction, but we now know them to be inaccurate. Films like the recent Jurassic World: Rebirth have played a part in cementing our idea of what dinosaurs look like – but just how true to life are these portrayals?

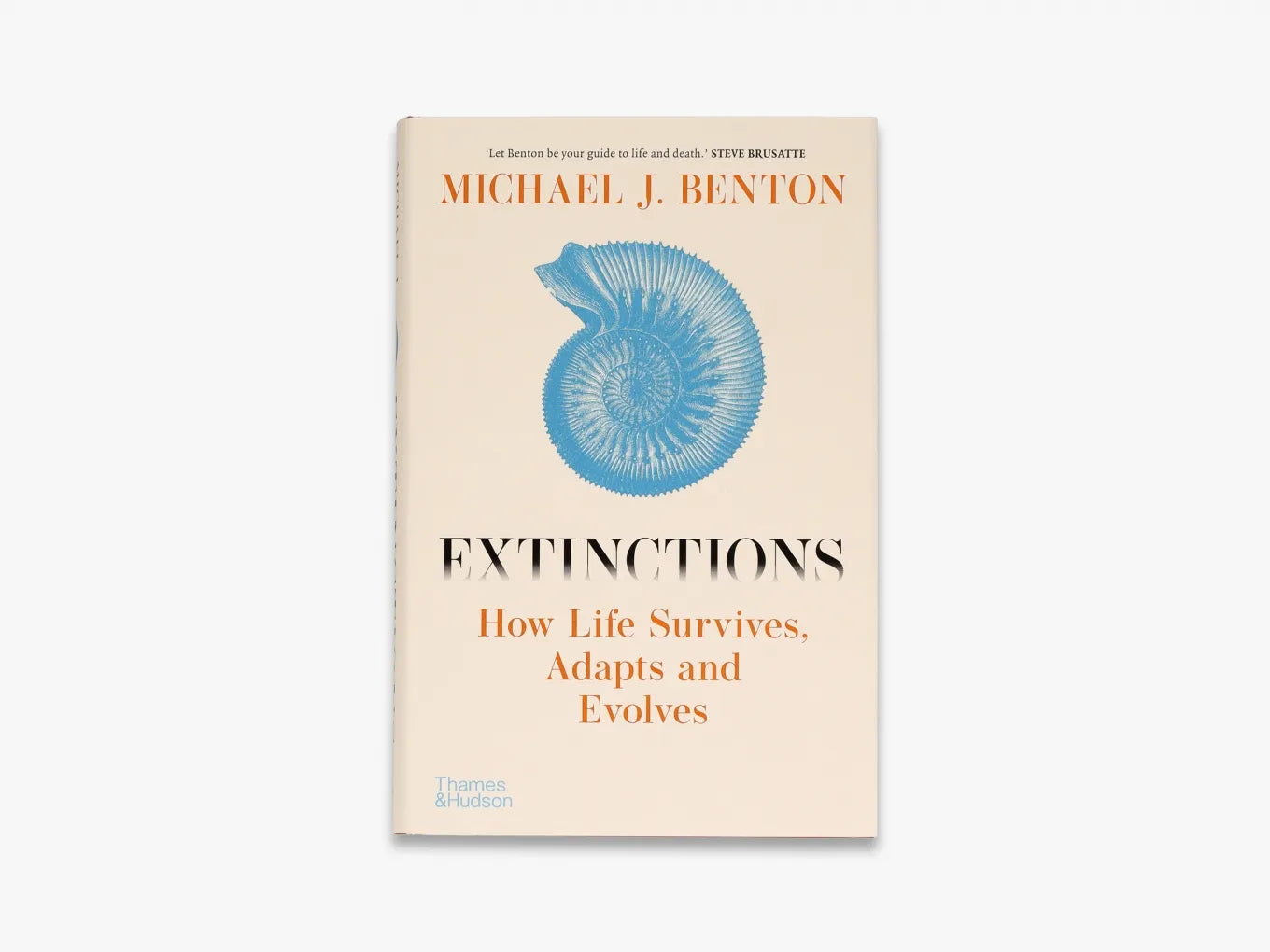

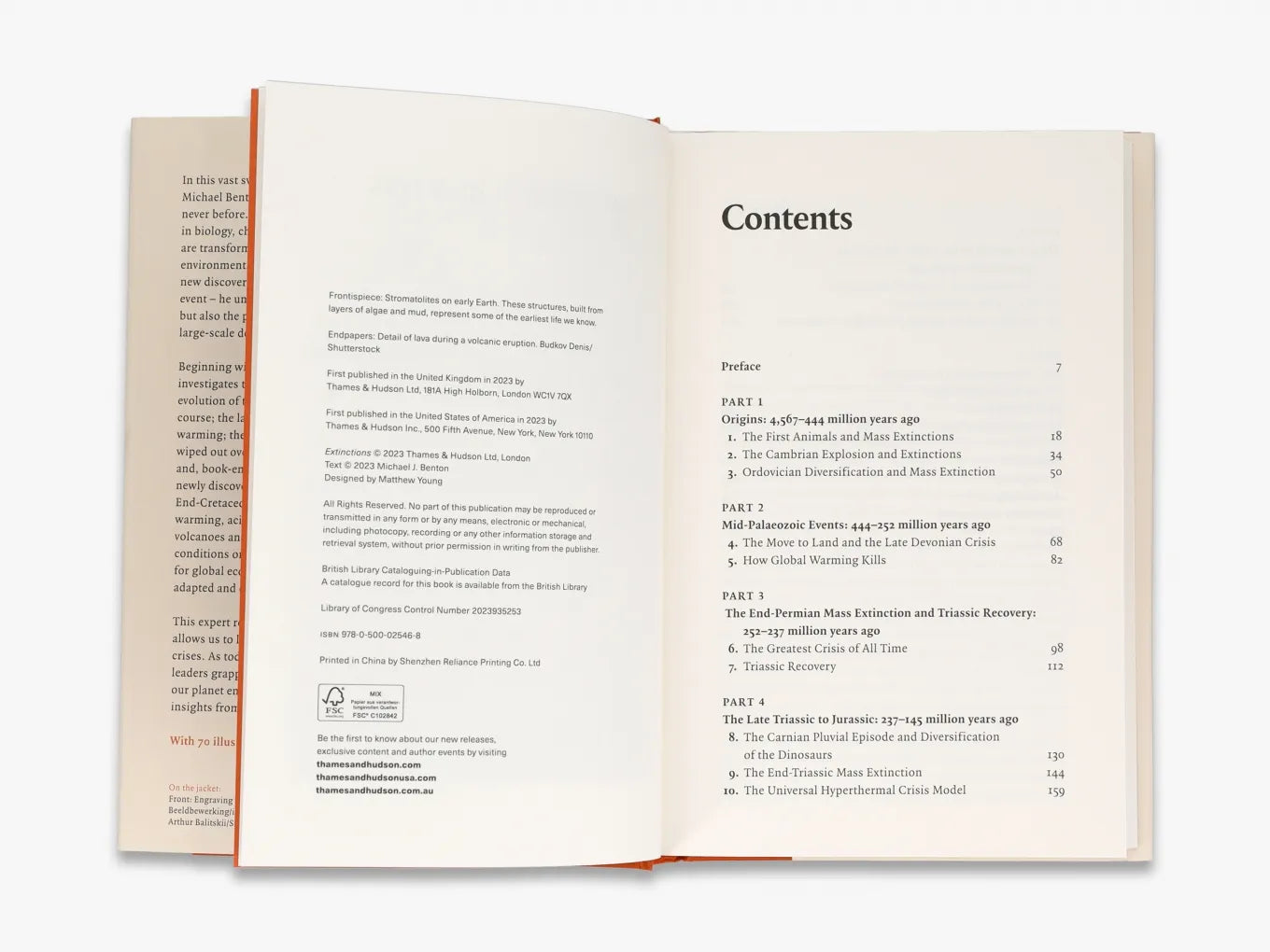

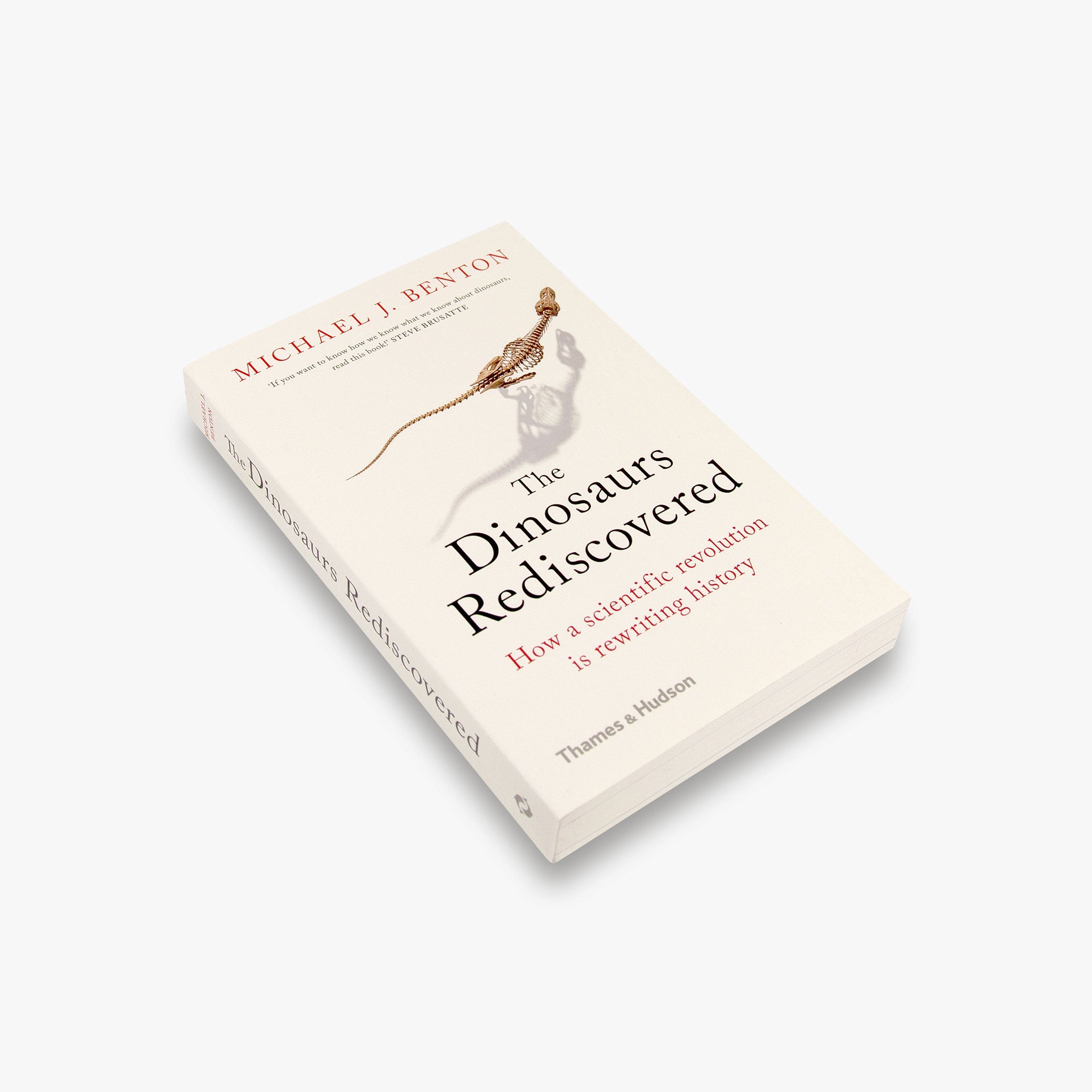

In Dinosaurs: New Visions of a Lost World, Michael J. Benton brings us a new visual guide to the world of the dinosaurs that surprises and challenges everything you thought you knew about what dinosaurs looked like and how they lived. Michael has been involved in many of these earth-shattering discoveries, including identifying the colour of dinosaur feathers for the first time, in 2010. Artist Bob Nicholls has also worked on dinosaur reconstructions for several of the key scientific papers in the past ten years.

We asked Michael about some of the myths and common beliefs many people have about dinosaurs, and what we can learn from this new research.

© Smithsonian Institution Archives. A skeletal restoration of Hadrosaurus foulkii in the United States National Museum (now the Arts and Industries Building), 1880, based on the original in the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences.

Until recently, palaeontologists had no way to know the colours and colour patterns that were displayed by ancient animals, and they thought they never would. Then, in 2010, two teams of researchers showed how to do it: exceptional fossils from China provided evidence of original colours deep in the structure of their preserved feathers. But why has our image of the dinosaur changed so much?

Changing fashions, changing dinosaurs

Two hundred years ago, when dinosaurs were first discovered, the palaeontologists had a number of ideas about what they were – giant lizards or crocodiles, or even some kind of super-sized reptilian rhinos. If you have seen the Crystal Palace dinosaurs in south London, or images of them, these show a very different understanding, dating back to 1853. At that time, Sir Richard Owen, the leading dinosaur expert in the UK at the time, thought that the giant bones came from strange race of warm-blooded behemoths, reptiles certainly, but strangely mammal-like in appearance. But he only had isolated bones and no complete skeletons.

© American Museum of Natural History. Leaping Laelaps, Charles Knight, 1897. Knight’s careful study of the anatomy and behaviour of living animals enlivened his sketches of extinct species.

Late in the 1800s, complete skeletons of dinosaurs from North America and Belgium showed that many dinosaurs were bipeds, standing up on their hind limbs, and using their hands to grab and balance. This of course changed the popular image and later finds from all over the world continued to add new species and new body shapes – think of the long-necked giant Diplodocus, the plate-backed Stegosaurus, and the terrifying Tyrannosaurus rex with its huge head, huge legs and tiny little arms!

To the public, the appearance of dinosaurs comes from palaeo-art, in the form of paintings or movies. The artists often strive to get it right and seek advice from palaeontologists. Appearances can change as new fossils are found, but also new discoveries about how dinosaurs lived. One hundred years ago, all the experts would have said that dinosaurs were cold-blooded, like lizards, and so they must have been slow-moving, lumbering creatures. But then, various discoveries since the 1970s – especially by looking at the microscopic structures within their bones – have shown that dinosaurs were actually warm-blooded, and the smaller ones at least could have hopped about and run quite fast.

Then came feathers.

From left to right: © Bob Nicholls. Archaeopteryx reconstruction / © Natural History Museum. The Berlin specimen of Archaeopteryx, collected from Solnhofen in 1874 or 1875.

Feathers and…

When the first Jurassic Park movie was made in 1993, the dinosaurs all had scaly skin. The first bird, Archaeopteryx, did not appear in the film, but it would have been shown with feathers, because the fossils show their plumage. Then in 1996, the first report came out of a Cretaceous dinosaur, Sinosauropteryx, with similar bristly feathers over much of its body.

This set the palaeontological cat among the pigeons. Some professors complained that a dinosaur could not have feathers – after all, only birds have feathers. But close inspection of the fossil showed that Sinosauropteryx was without doubt a dinosaur, not a bird, and other professors reminded the doubters that birds evolved from such dinosaurs. So, now it is widely accepted that dinosaurs might well all have had feathers right from the beginning. And indeed, since 1996, thousands of fossils have come to light showing feathers preserved in the remains of dozens of species of dinosaurs.

What more have we learned from these fossil feathers? First, it seems that dinosaurs could have many different kinds of feathers, including all the whiskers, down feathers and flight feathers seen in modern birds, plus more. Some dinosaurs sported long ribbon-like feathers; others had feathers like flags on the end of long quills, and others had part-scale, part-feather structures.

© Bob Nicholls. Sinosauropteryx snatches lizard Dalinghosaurus from a small pool and shakes it. Dinosaurs did not chew their food, so he grabs the prey animal, twists it round so it faces head-first and gulps it down. This is why there is a whole lizard skeleton inside the guts of one of the museum

…Colours

Deep inside the fossil feathers are specialized capsule structures called melanosomes that store pigments. By comparison with modern birds, these melanosomes in the fossils can indicate the actual colours exhibited by the dinosaurs in life, as well as the patterns shown by those colours in combination – such as ginger and white stripes, pale spots on black backgrounds, reddish crests and many more.

It was a surprise to find that many dinosaurs had bright colours and patterns that were used for display. The stripes, spangles and spots are on feathers of the tail and wing, and crests on top of the head. Just like some modern birds, these dinosaurs probably hopped and dipped, ruffling their feathers and flashing impressive displays at potential mates.

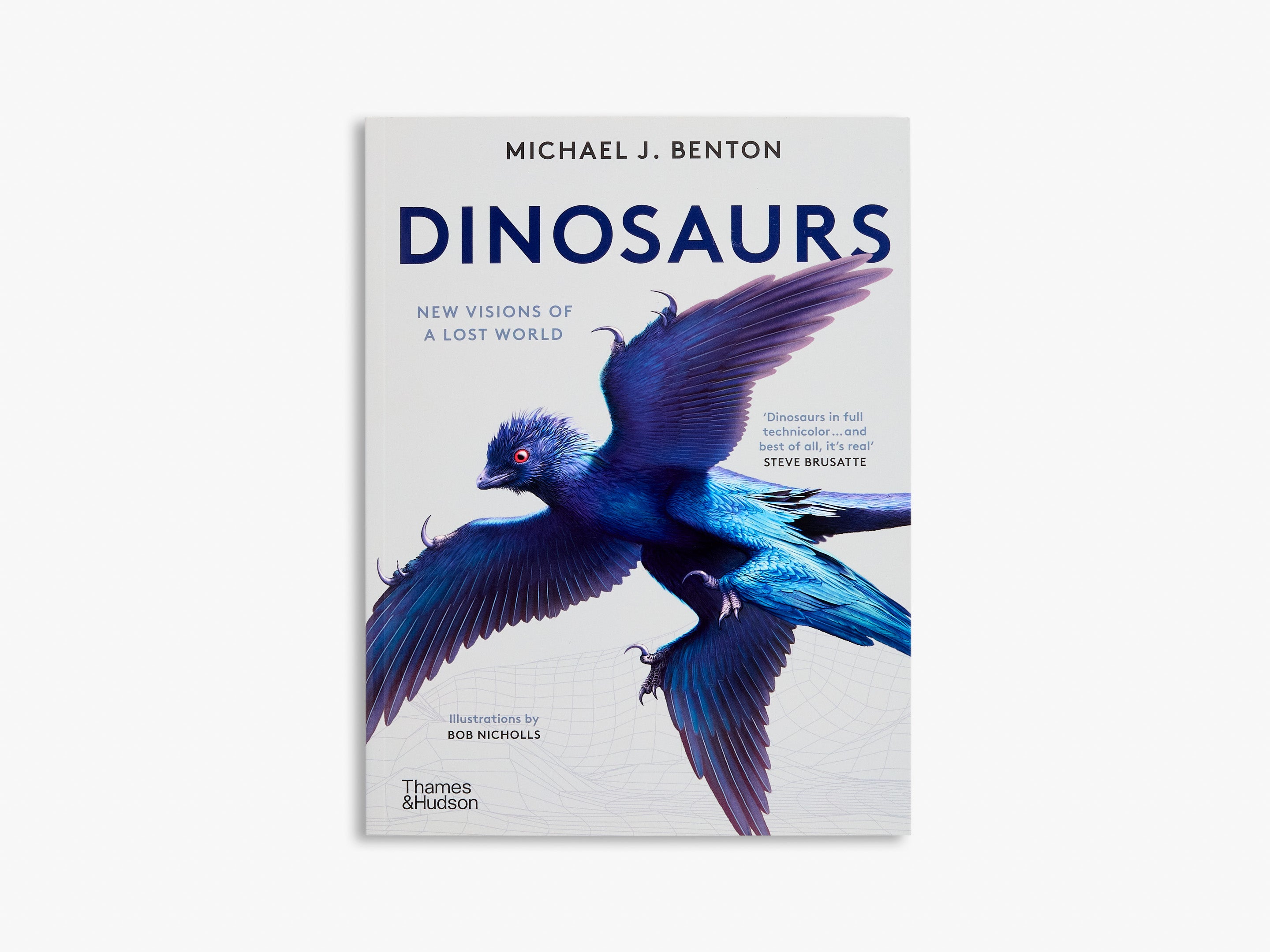

© Bob Nicholls Edmontosaurus reconstruction

Indeed, very large dinosaurs might have had limited feathers, maybe just some tufts on their heads or tails for display purposes. Large mammals like elephants and rhinos have plenty of hair as babies, but lose their hair as they grow, because their bodies are so huge they do not need the extra insulation in hot countries. This might have been true for the large dinosaurs. Some dinosaurs like the duck-billed Edmontosaurus have left fossils of their mummified bodies in the ancient sands. These impressions show that their skin was covered by scales in places, and bony plates in others. The horny coverings over their scales show evidence of gingery colours in life.

A remarkably complete specimen of the early horned dinosaur Psittacosaurus shows some very strange reed-like feathers in a row down the middle of the tail, and that the skin was pale underneath and marked with a spatter of dark markings. The pale colour underneath was countershading, just as in modern animals that live in brightly lit woodlands. The pale-below, dark-above pattern minimizes contrast and ‘flattens’ the body when viewed in the dappled woodland light which is bright above and shadowy below. A two-dimensional herbivore is harder for a carnivore to spot than a three-dimensional prey animal.

From left to right: © De Agostini Picture Library/Diomedia Images The adult Psittacosaurus skull shows the deep jaws lined with chopping teeth. There are no teeth at the front of the jaws, so this animal presumably fed on tough vegetation that it cropped with its bony, horn-covered beak. / © Bob Nicholls Psittacosaurus reconstruction

Advancing science, changing appearances

This new vision of dinosaurs marks a huge step forward. Many will be familiar with traditional images of dinosaurs, often with scaly, green, grey or brown skins. Over the decades since dinosaurs were first discovered, their appearance has been debated, and images have evolved as new evidence has emerged. Knowing how dinosaurs functioned and behaved has profound implications for our wider appreciation of the life of the past.

Dinosaurs matter. They are not just for kids. It’s worth remembering that dinosaurs were huge, and they were successful, living on the Earth for over 170 million years. The largest dinosaurs weighed 50 tonnes, ten times the size of the largest land animals today, the elephants. And yet the world in the Jurassic was more or less the same as it is today. How did those giants move, how did they feed themselves, and how did they reproduce?

Gone are the days when scientists and educators have had to answer all the pressing questions from children and others with a shrug of the shoulders or a guess. Now, we can give direct answers supported by evidence. What better way to spark the excitement of wonder in enquiring young minds?

Words by Michael J. Benton

Discover Dinosaurs: New Visions of a Lost World now