Published to celebrate the 250th anniversary of John Constable’s birth, Constable’s Year offers a fresh perspective on the life and work of the artist. Susan Owens closely examines the ways in which the yearly cycles of weather and agriculture – and the often-competing demands of the art world – resonated with the artist. Whether in London in May, preparing pictures for exhibition and longing for the Suffolk spring, or painting boat-builders and waiting to be married in a particularly gloomy September, Constable’s life and work were unusually shaped by the seasons.

Ahead of publication, we asked Susan to share her thoughts on Constable’s enduring legacyand explain why viewing his work through the lens of the passing seasons allows for a deeper appreciation and understanding of his artistry.

Hampstead Heath, looking towards Harrow, at sunset, 12 September 1821. Oil on paper, 24.1 x 29.2 cm (9 1/2 x 11 1/2 in). Private collection

The strange thing about Constable is that people often think of him as a traditional artist – even the traditional artist par excellence. I used to think the same. When I became Curator of Paintings at the V&A, which holds the most extensive collection of works by Constable in the world, I felt almost intimidated by the thought of having to take on this huge, establishment figure. It only took a day or two for that to change. I realised he was not traditional at all: he was radical.

I remember going into the museum’s paintings galleries where Constable’s oil sketches are always displayed – I am not talking about his exhibition pictures here, but the rapid studies he made directly from nature, which he never intended anyone to see. I stood in front of one, a study of the trunk of an elm tree, and I could not take my eyes off it. It is an astonishing little painting. The detail is riveting, the sense that Constable had really looked, harder than anyone had ever looked at bark before. Not only that, but that he had understood the essence of that tree. He didn’t fall back on artistic convention, as other landscape painters of his generation would have done: he translated what he saw into paint with all the dogged faithfulness he could muster.

Constable had immense respect for the natural world, born of his farming background. A friend of his even remembered him lying down underneath trees to study the movement of their branches as they swayed in the breeze. He wanted to paint nature as it appeared under English skies.

A Cloud Study, Sunset, ca. 1821. Oil on paper on millboard, 15.2 x 24.1 cm (6 x 9 1/2 in). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, New Haven, CT

The next thing that struck me at the V&A, once I had spent more time with his drawings, sketches and finished paintings, was that Constable was always re-thinking his approach. Always. He never settled for a saleable formula. He was like Picasso in that way – you can see his work constantly evolving, waves of new ideas and methods transforming it. When Constable was in his thirties, he went through a period of intense realism, taking his easel outdoors to paint every leaf.

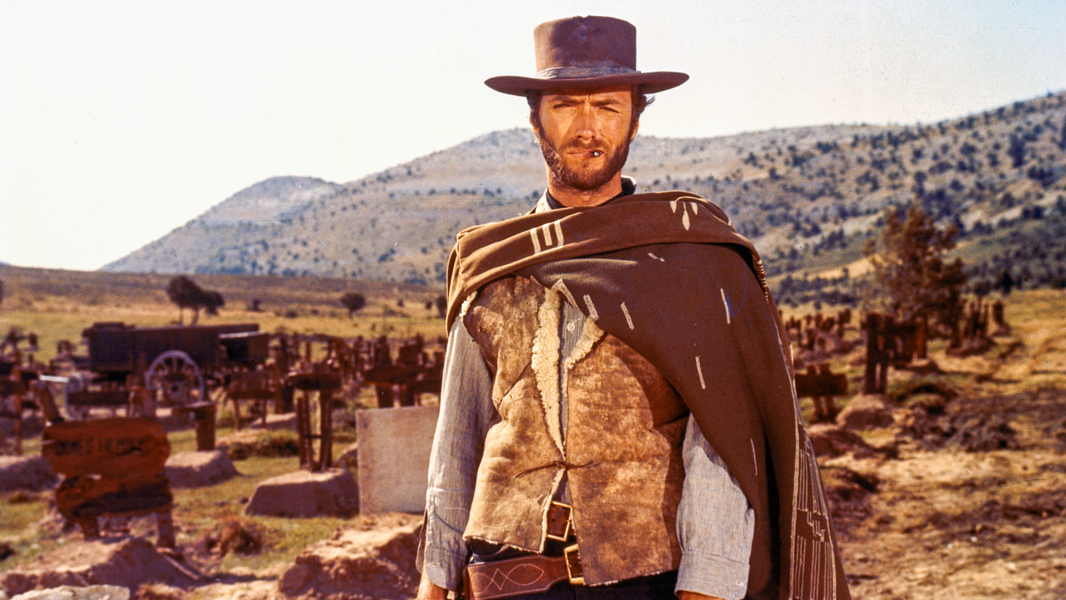

Later in life, his paintings, by then made in the studio, become more expressive, sometimes wildly so. There is one you could mistake for a Jackson Pollock. These late pictures are as much about memory and emotion as observation. But it was observation that underpinned it all. At a certain point, he felt he wasn’t getting skies right, so over the course of two successive autumns he made an intensive study of the clouds over Hampstead Heath, day after day, adding detailed notes of time and weather to the backs of his sketches.

Constable had boundless curiosity and a driving ambition to improve. That is why so many of his contemporaries – artists who produced conventional pictures, and as a result were more successful than him in their day – have been forgotten, while people still love Constable’s paintings. Many of us stand in front of them today and absorb the profound truths they reveal about landscape, place and feeling.

Hadleigh Castle, 1829. Oil on canvas, 122 x 164.5 cm (48 1/8 x 64 7/8 in). Yale Center for British Art

Why did I choose to frame Constable’s Year around the seasons? After I moved to the Suffolk countryside – not far, in fact, from East Bergholt where Constable grew up – I became acutely aware of the turning of the year, especially with the all too visible disruption brought by climate change. I had also been thinking a lot about Constable, and I became increasingly interested in how he had responded to each season and the weather it brought – a subject no previous writer had focused on. I wanted to discover what he had done at different times of year and what each season meant to him, both personally and professionally. I had previously associated him with high summer, but I thought: there must be another story. I was right. Looking at Constable’s life and work through a seasonal lens has been exceptionally revealing about his attitudes to nature and his complex relationships with particular places. His emotional life, too.

The rectory from East Bergholt House, 1810. Oil on canvas laid on panel, 15.6 x 24.8 cm (6 1/4 x 9 7/8 in). Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection

Constable adored spring. Sadly for him, he was normally stuck in London for the opening of the Royal Academy exhibition on the first Monday in May, the pivotal moment of the year for artists in his day. But when he did manage to get back to Suffolk then, he would exclaim every time that it was the best year yet for blossom and he had never in his life seen such beauty. In summer, he roamed the lanes, fields and towpaths and made the drawings and sparkling oil sketches that connected him to the natural world: they fed the exhibition pictures that he painted in his studio during the short, chilly days of a London winter.

What surprised me was his attitude to autumn, which is best described as ambivalent. One October day found him complaining to a friend about the ‘rotting melancholy dissolution’ of the trees on Hampstead Heath. Two years earlier, though, he had told the same friend he had been walking on the heath all day and could hardly paint for looking, so beautiful was the autumnal scenery. The glorious painting he made that day is so ravishing I can hardly stop looking at it myself. I asked if we could use it as the frontispiece.

Cloud study, 25 September 1821. Oil on paper, 21.2 x 29 cm (8 3/8 x 11 1/2 in). Yale Center for British Art

I was quite ‘method’ with this book, writing each chapter in its relevant season. I began ‘Spring’, in a mild, blustery March and completed ‘Winter’ just as February brought the first brighter days to what had been a particularly cold, damp season. Immersed in Constable’s letters as the seasons turned, I read about his joy in hearing skylarks in April, the pleasure he took in a long walk on a summer’s day and his mixed emotions at the onset of winter. How he folded these feelings into his paintings is at the heart of Constable’s Year.

Words by Susan Owens