Trench de Vie - AW 1983. © Paul van Riel.

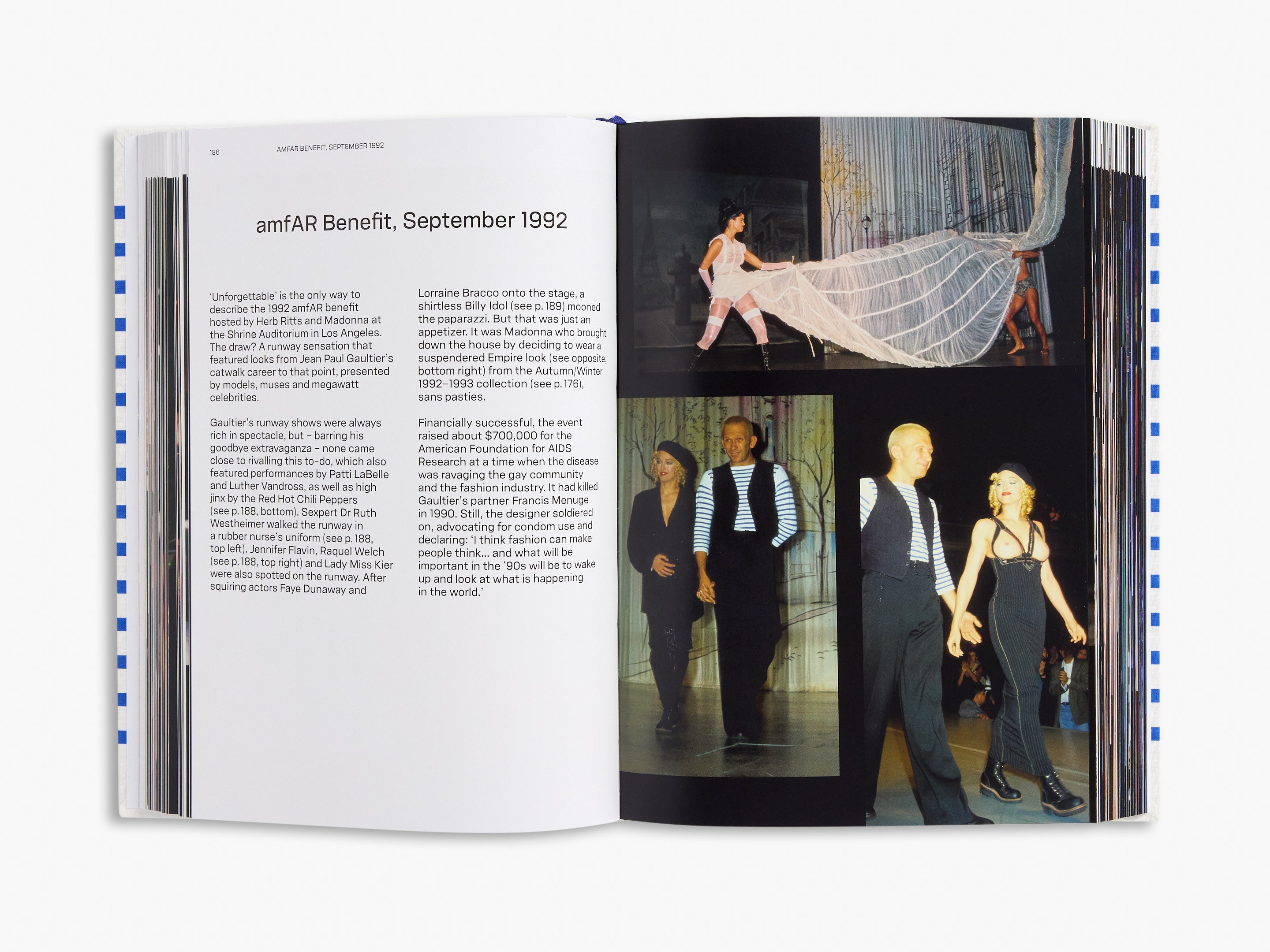

In his own way, Jean Paul Gaultier has become as associated with France, and sexuality, as the blonde bombshell Brigitte Bardot. Yet his is an alternative universe, in which attraction and identity are seen with a queer eye and from an outsider’s perspective. The doe-eyed ingénue is an exemplar of heteronormative attractiveness, in which women are placed on a pedestal; Gaultier’s understanding of gender is more fluid and more egalitarian. Bardot is eternally associated with a teeny-weeny gingham bikini: topping a long list of Gaultierisms are striped marinières, trench coats, corsets and skirts for men. All of which – and so much more – you’ll discover as you look through the designer’s ready-to-wear and couture collections from 1976 to 2020.

If you had asked me, before I started writing this book, to share the first things that came to mind at the mention of the name Gaultier, my list would have included the designer’s 1990 Pierre et Gilles portrait, complete with Eiffel Tower and daisies – an indelible and nuanced post-modern image informed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s homoerotic film Querelle (1982).

Specific collections, looks and muses would, of course, be right up there: Julia Schönberg in marabou-trimmed denim (see p. 289, left), the ‘Tattoos’ collection (p. 198), Madonna closing a show pushing a baby carriage (p. 215), Tanel Bedrossiantz in 18thcentury-inspired dress (p. 264), Chrystèle Saint Louis Augustin with a beaded ship in her hair (p. 263, left) and a tight-laced Suzanne Von Aichinger (p. 360), plus editors coming back from Paris with the most beautifully tailored Gaultier blazers. I would have talked to you about how the designer seems to have done everything first, about how his vision was inclusive and broad. And it is impossible to speak of Gaultier without recognizing his sunniness, his sense of humour, and his penchant for high camp.

Ask me now, after poring over thousands of images and hundreds of newspaper articles, and I’d add quite a few things. Added to my visual memory is an image of Anna Pawlowski, the designer’s early muse, sporting a tutu and motorcycle jacket, like some latter-day Degas, in Gaultier’s debut collection (see p. 26), held in a planetarium (a portent of his future stardom?). That look feels so important because it sets up many of the dichotomies that would become codified over the years. There is tailoring and flou (the traditional binary by which couture houses are organized); street/salon; punk/pretty; past/present; and androgyny.

From left to right: Virgins - SS 2007. © firstVIEW / Launchmetrics Spotlight / Rock N Romantic - SS 2011. © firstVIEW / Launchmetrics Spotlight

The collision of such opposing forces resulted in aesthetic fireworks. Just as interesting is the way Gaultier worked behind the scenes, flattening hierarchies and challenging the way things had always been done. An early champion of ready-to-wear, he had a trickle-up way of working. Not only did he bring trends that started on the streets (and in the clubs) to the runway, he also started with prêt-à-porter and then went into couture, reversing the usual course. Looking through the collections you can readily observe the fluid transfer of ideas and techniques between the two types of fashion. The collection notes shared with me by the house gave testament to how designs and materials were altered, and reused, long before the designer described his final Spring/ Summer 2020 collection as the ‘first upcycling haute couture collection’. Think of it as the post-modern mix applied to materials and objects rather than aesthetics, references and ideas.

Gaultier’s runway antics are legion – he once gave interviews at a show from a magician’s box in which only his head appeared – and it has often been assumed that his m.o. was to épater les bourgeois. There’s an element of this, of course, but as we’ll discuss further on, what really drives the designer is a wholesale rejection of bourgeois values. In practice, Gaultier’s ‘free to be you and me’ beliefs truly embody the age-old, and noble, French ideals of liberté, égalité, fraternité.

Jean Paul Gaultier was born on 24 April 1952 in the suburb of Arcueil, located about 20 kilometres away from the Eiffel Tower (which would become one of the designer’s favourite motifs). As the only son of an accountant and a clerk, Gaultier’s origins are lower-middle-class, in a culture in which status matters. Yet the designers in history he is most akin to are the cosseted, Proustloving Yves Saint Laurent and the aristocratic Elsa Schiaparelli.

Not only was the young Frenchman at a physical remove from Paris, but his homosexuality and a feeling of otherness (which sometimes converged) contributed to a sense of difference, which he would turn into his superpower. When it came time to establish his own maison de couture, Gaultier maintained, by choice, a geographical separation from luxury’s ‘Golden Triangle’; his first boutique opened in the Galerie Vivienne covered arcade in 1986, and later he situated his headquarters in the ‘Proletariat Palace’, a former worker’s club (among other things), at 325 rue Saint-Martin.

Biker of the Opera - SS 1977. Courtesy Jean Paul Gaultier

The designer started visiting London in the 1970s, and Franglais was his preferred tongue, especially at the start of his career. He felt a sense of solidarity with the punks, adopting the motto ‘too fast to live, too young to die’, and later with the New Romantics. ‘I love the eccentricity and the freedom [of London],’ the designer has said. ‘Whereas in France we are a little bourgeois: there’s no sense of humour, no sense of self-criticism. You have always to be so nice and so elegant. Truly, I hate that, and I love that in England there is a contrast: fantasy is completely accepted.’ And DIY was a default practice – one that Gaultier adopted, most obviously in the early years, showing jewelry made of tin cans and tea infusers, and garments of rattan place mats, in the best punk tradition.

From 1993 to 1996, the designer’s cross-cultural diplomacy expanded to include a co-presenter role, with Antoine de Caunes, on the British TV series Eurotrash. By the time he appeared on the show, Gaultier was a household name – having been launched into the stratosphere by his collaboration with Madonna for her 1990 Blond Ambition tour. He had also settled into his public persona and a signature look. In 1989, he had released his own dance single: titled ‘How To Do That’, in which ‘that’ is pronounced like ‘zat’, it played on his purposely exaggerated accent. By now he wore his blond hair shaved short, had three silver hoops piercing his right earlobe, and was usually to be seen in a plaid kilt – a look he had introduced as early as Autumn/Winter 1980–81 and made as iconic a Gaultierism as the Querelle-inspired striped marinière shirts that were the centrepiece of his 1983 ‘L’Homme Objet’ collection. With the kilt, Gaultier often wore a second-skin ‘tattoo’ shirt, and accessorized with biker boots of the sort drawn by Tom of Finland. In effect, he ‘outed’ – and normalized – elements of what had been a coded gay uniform, not only on the runway but also through his personal style.

The designer did something similar with shape and support garments, taking lingerie out from under to stand on its own; exposing what lies beneath – or what seems to. (Gaultier loves a visual gag, and his anatomical trompe-l’oeil prints are by now signature.) One of his great accomplishments is this kind of inversion, this upending, topsy-turvy approach, which forces people to face their biases and challenge their assumptions. And he puts this into practice on ideological and material levels using his technical skills: inside-out construction is one example.

Haute Couture Salon Atmosphere - SS 1997. © firstVIEW / Launchmetrics Spotlight

It’s been said that what Yves Saint Laurent accomplished through design in terms of women’s liberation, Gaultier did for men. Putting them in skirts – which was shocking at the time – was not at all an attempt to feminize the ‘stronger sex’, but rather to put them on a pedestal, Bardot-style, in a way that benefitted everyone. In theory, Gaultier was always moving in the direction of true gender egalitarianism. ‘My clothes are not about androgyny, not about uni-sex; they are about sexual equality,’ he told The Observer in 1984. ‘Men can be glamorous, they can be fragile and beautiful too. They have to be sexy and seductive today. Women are waiting for that.’

Unity and difference – or perhaps unity in difference, given the existence of Gaultier’s semi-autobiographical revue Fashion Freak Show – are subject(s) the designer is always grappling with. Another preoccupation is the construction of the self through the transformation of the body – be that through makeup application, posture and gesture, body modification, or decoration. There’s an underlying sense that you build a look like you would a time-travelling travel itinerary, pulling a bit from here, there and everywhere – with the meaning being in the individual amalgamate. Much as the designer advocated for equity in gender relations, so he did for a ‘melting pot’ view of culture. ‘I take into consideration today’s life. Today, people have a need to be more individualistic,’ he told Newsday in 1984. ‘Also, I travel a lot and I think that now everybody travels a lot, so there is a mixture of cultures and some culture shock. That is what’s interesting now….. Culturally, the world is getting much smaller, so it’s more important to be flexible.’

Fashion writer Liana Satenstein has dubbed Gaultier ‘the original cultural appreciator’. Critics of the 1993 ‘Chic Rabbis’ collection, for example, might use the word ‘appropriator’ instead. ‘I’m not sure you could do something like that today,’ Gaultier stated in a 2023 interview, in which he also said: ‘I really think it’s always about someone else, about seeing someone who’s inspiring and completely of a moment. I think that’s how we’re made: we see something, and then we re-offer what we’ve seen.’ The thing is that Gaultier was looking in places and elevating people and traditions that other people weren’t.

Gaultier’s global vision was in sync with an MTV world in a way that was unusual. For him, a Parisienne could be a Birkin-carrying denizen of the Right Bank, or a woman from the banlieue; a cyber nun, or a latter-day cancan-dancing Jane Avril. In rejecting standardized ideals, Gaultier was championing different kinds of beauty in terms of ethnicity, size, age, ability, sexual orientation and body modification. You would not find such references, or casting, anywhere else in Paris.

From left to right: French Can Can - AW 1991. Guy Marineau & Etienne Tordoir / Catwalkpictures / Gaultier Classics Revisited - SS 1993. Guy Marineau & Etienne Tordoir / Catwalkpictures

Gaultier is responsible for many firsts – firsts that we take for granted, such as street casting. ‘We’re all little children of Jean Paul Gaultier,’ designer Nicolas Ghesquière (who got his start with Gaultier as an 18-year-old paid intern) has said. Speaking with The New York Times, he described Gaultier as ‘a “master of everything”’, who ‘broke boundaries we’re now all able to explore’.

The designer’s many and varied experiences have placed him in a stratosphere that exists beyond hyphenates, which, by the way, haven’t stopped accumulating with the designer’s retirement (from the runway only) in 2020. Although there are almost innumerable ways to describe and refer to Gaultier, one moniker has defied time and stuck like a tattoo: the designer will forever be known as fashion’s enfant terrible.

Among the definitions the Merriam-Webster dictionary gives for the appellation are: 1) ‘a person known for shocking remarks or outrageous behavior’; and 2) ‘a usually young and successful person who is strikingly unorthodox, innovative, or avant-garde’. It is true that Gaultier flew by the seat of his pants at the start; but that was as much out of necessity (his budget was near to zero) as inclination. How did the designer develop such a proclivity?

Well, before he became the archetypal post-modern designer, Gaultier was a post-war baby. The armistice ending the Second World War was signed in 1945, but Paris in 1952 was far from dazzling. Lyla Blake Ward, an American who arrived in the capital about a month before Gaultier was born, gave this account:

Expecting beauty and light in a city with echoes of Victor Hugo, Degas and Maurice Chevalier, we got somber darkness and bone chilling weather. We drove through grim streets, rundown houses on either sid... Notwithstanding the gloomy weather, it was heartbreakingly apparent France had still not gotten her act together. In 1952, six and a half years after the end of World War II, the grime of war coated even the most beautiful buildings, causing them to appear proud but worn. The Louvre, Notre Dame and Sacré Coeur were like elderly actors who hadn’t worked for a long time.

This isn’t something that the designer has spoken much about, but certainly his parents and grandparents lived through the war and severe rationing, and it’s not a stretch to think that the ‘make do and mend’ philosophy Gaultier adopted at the start of his career was an extension of an ethos Parisians had to follow.

Adversity breeds the need for escapism. As a child, Gaultier had several sources of entertainment. There was Nana, his famous teddy bear, who was subjected to all sorts of modish experiments, but no one had more influence on the young Jean Paul than his maternal grandmother, Marie Garrabé. In addition to the corset she wore, which influenced some of Gaultier’s most memorable designs, Madame Garrabé wore many proverbial hats, offering beauty treatments and ersatz therapy at her home. It was chez Garrabe that Gaultier observed how dress can be transformative – and not only of the body, mood, mind and mien.

At grand-mère’s home, Gaultier also had access to a world beyond the ordinary via television. That magic box allowed him to watch fashion reportage, the Folies Bergère (references to which are frequent in the designer’s work) and many movies. None was more impactful than Falbalas (Paris Frills), made in 1945. ‘Seeing Jacques Becker’s film ... was a turning point for me, as I realized that I wanted to be a couturier. Watching the fashion show at the end of the film, I just knew that presenting shows was what I wanted to do. That is why my fashion shows were always a bit cinematic,’ Gaultier told Vogue in 2024.

Europe of the Future - AW 1992. Niall McInerney / Bloomsbury / Launchmetrics / Spotlight

In the film, which features a lifelike mannequin, boundaries between fantasy and reality are blurred. What you see isn’t always what you get in Gaultier’s world either, and not only when he leans into trompe-l’oeil effects. He once created a light-up Pigalle-themed dress (see p. 312), and many of his designs were transformative: a pouch might turn into a skirt, the front and the back of an outfit might be different, and the same design could be sent down the runway on models of different genders. The performative aspect of dressing and of creating a persona are key to the designer’s oeuvre for runway, stage and screen. Gaultier costumed a number of films, among them Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989), Pedro Almodóvar’s Kika (1993) and Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element (1997).

But we are jumping ahead. Gaultier started making fashion sketches as a boy, and his entry into fashion was quite traditional. Like Christian Dior and so many before him, Gaultier submitted the drawings he made as proposals to the maisons de couture. As the story goes, in 1970, on his 18th birthday, Gaultier was hired as an assistant by Pierre Cardin. While, in her New Yorker profile, Susan Orlean suggests that it was Gaultier’s stint at the more traditional house of Patou that hewed most closely to his Falbalas dreams, on paper the pairing with Cardin reads like kismet. ‘At Cardin everything was possible,’ Gaultier has said. ‘The atmosphere was very open, very free. He...did not have the concept of an old couture house, the old concept that you cannot do this, you cannot do that. You could do whatever you wanted.’ The same words could be applied to Gaultier himself.

Gaultier shares in common with Cardin a penchant for futurism and unisex dressing. Arguably their most important commonality is a belief in ready-to-wear. In 1959, the Italo-French Cardin (who had worked on Christian Dior’s 1947 ‘New Look’ collection) was expelled from the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture for producing a prêt-à-porter collection. It was a time of transition, marked by the age of travel and the dawning of the Youthquake, which would usher in a new, faster-paced and more casual lifestyle that was less compatible with the timely, in-person fittings that couture requires. The organization’s resistance against this new category of dress was longstanding; it was only in 1973 that the Chambre Syndicale recognized prêt-à-porter, just three years prior to Gaultier’s debut.

Buttons - SS 2003. © firstVIEW / Launchmetrics Spotlight

The designer had spent the previous year (1974–75) working for Cardin in the Philippines. Put on a ‘no leave’ list, he managed to get back to France by fibbing and saying his grandmother was dying. Back home he was encouraged by Francis Menuge, his life and business partner, to give it a go on his own. So, with the help of family and friends, Gaultier presented ‘Biker of the Opera’. The collection, which featured the punk ballerina look mentioned above, and a long, tri-partite silhouette (small top, with skirt suspended from hips, so that a slash of skin was visible above the top of the skirt), was DIY and distinctly not couture. Yet in Gaultier’s worldview, the glass is always half full: this wasn’t so much a rejection of high fashion as an embrace of a new way of thinking from an up-and-comer of the post-war generation.

Over time, Gaultier became an outsider-insider – a status linked to his decision to take on the couture (debuting with the Spring/ Summer 1997 couture season), fulfilling one of his and Menuge’s dreams. Later, following in the footsteps of his one-time assistant, Martin Margiela, Gaultier would become a creative director at Hermès (2003–10), whose accessories are the utmost expression of French savoir-faire. For all his rebelliousness, Gaultier, a largely self-taught designer, has a deep respect for the métier. I hope you’ll take as much delight as I did in observing the superb quality of his work, and the way the excellence of his technique is used to create a contemporary vocabulary.

The brand’s ready-to-wear operations shuttered in 2015, after which Gaultier concentrated on couture, presenting his final blow-out collection for Spring/Summer 2020. This marked his retirement from making collections, but not from work. Executing an idea he had almost 40 years earlier when he was at Patou, Gaultier initiated a guest couturier programme – meaning that each season he invites a designer to create a couture collection based on the Gaultier archive. This has been a fantastic success, and one that keeps the house always in the news.

Concurrently a whole new generation of fashion lovers has discovered Gaultier’s work, creating a demand for vintage, reissues and reinterpretations. Yet worldly status has never been Gaultier’s driver. Was it a coincidence that he started in 1976, the year that America celebrated her independence? Though he was never a hippie, freedom is this designer’s grail. As Gaultier said: ‘[I]t is not that I want to be the first one or to be the best one, it is only that I want to make what I like.’ This book nonetheless shows that he achieved the whole trinity.

Words by Laird Borrelli-Persson

Jean Paul Gaultier: The Complete Collections is available now