The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the V&A, acquired with the generous assistance of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Art Fund © Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn / The Universal Order. Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882–1966) F. Holland Day, 1900. Gum platinum print, 11.4 × 14.8 cm

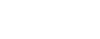

Calling the Shots: A Queer History of Photography draws on the collection held at the Victoria and Albert Museum – one of the oldest and largest in the world – to offer an unprecedented view of photographic history through a queer lens. It includes a broad range of global LGBTIQ+ representation from the mid-19th century to now, presenting images from pioneering LGBTIQ+ photographers and subjects alongside work documenting activism and hard-won legal battles, over a century of performance and nightlife and diverse queer communities, collectives and subcultures.

In this extract from the book, contributor Lydia Caston examines the role that fantasy and ‘the stage’ play in photography. These constructed images represent both a record and a possibility, allowing artist and subject to engage with their identities in both poignant and provocative ways.

Given by Eileen Hose © Estate of Dorothy Wilding. Dorothy Wilding (1893–1976), Cecil Beaton, 1925. Gelatin silver print, 31 × 24.5 cm

Imagination and fantasy have long existed as destinations of queer possibility. Since the invention of photography in the late 1830s, its performative potential has made it a vital medium for LGBTIQ+ artists engaging with provocative and challenging topics and deploying humour, irony and improvisation. Such images can act as document and fabrication, both a record and a possibility. For the photographer Deborah Bright, who stages satirical, poignant images, fiction is attached to the joy of the queer experience and helps to construct ‘social and psychic selves before the camera.’

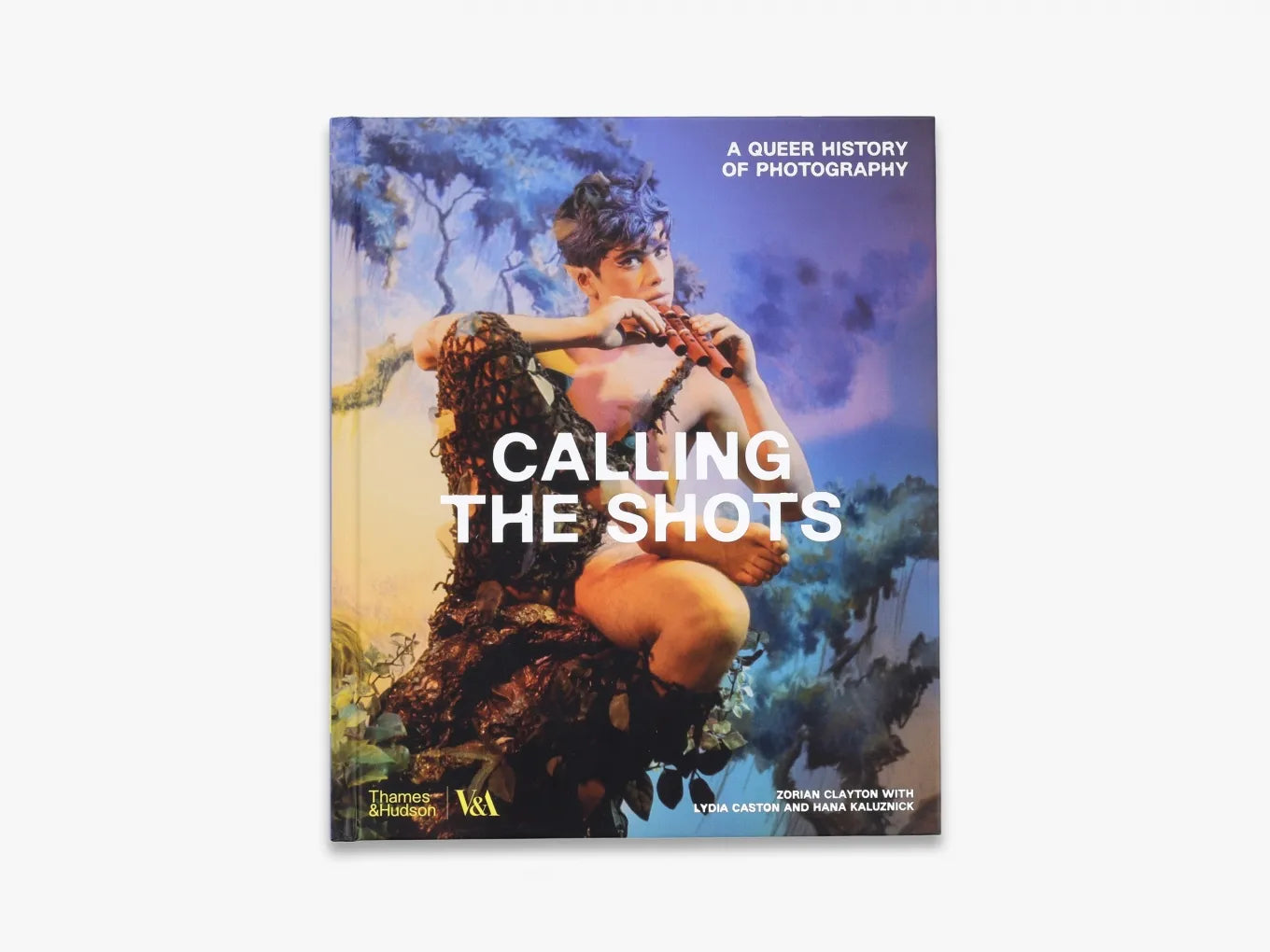

Staging scenes has enabled artists to create new forms of visual critique, often alluding to the constructed nature of identities through familiar stories. Tessa Boffin’s The Knight’s Move (1990) conjures a fictional world in which heterosexual romantic tales are led by lesbian protagonists such as The Casanova or The Angel. In 1998, Yinka Shonibare CBE played the part of the social-climbing Victorian dandy to explore his own identity in an imagined setting fit for today’s popular period dramas. A pivotal moment for this mode of performative photography was the 1920s and ’30s, a period characterized by a widespread fascination with artifice, magic and metamorphosis.

Purchased with the support of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and the Photographs Acquisition Group © Yinka Shonibare CBE. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2023. Yinka Shonibare CBE (b.1962). Diary of a Victorian Dandy: 14.00 hours, 1998. Chromogenic print, 134.5 × 195.5 cm

Surrealists often staged themselves as the protagonists of their works, imbuing their images with humour and an erotic undertone. Pierre Molinier, a part of this radical art movement in the early twentieth century, created his most provocative works in 1965. His self-portraits, made in his boudoir-atelier, rely on his fluid adoption of various alter egos for the camera, confidently posing in lingerie and stilettos. The photographer’s studio became a safe haven for experimentation, a space to perform privately and shed socially prescribed clothing and behaviour. Molinier’s images are a gesture of self-actualization, putting the artist-sitter forward as they might wish or want to be perceived.

Fantasy and camp creativity take centre stage in constructed images. A sexy satirical postcard from Paris in the 1910s portrays a pair of nearly identical female boxers, their open blouses revealing a comically calculated ‘nip slip’. In 1925, society photographer Dorothy Wilding captured the master of camp costume and playful excess Cecil Beaton in drag, his perfectly coiffed hair fashioned under an oversized floppy hat. Three years later, she snapped a nude female model floating on translucent bubbles, an image that likely inspired Beaton’s pictures of balloons and Bright Young Things.

Given by The Harold and Esther Edgerton Family Foundation, © Harold Edgerton/MIT, courtesy of Palm Press, Inc. Photo: Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of The Harold and Esther Edgerton Family Foundation,1996, 1996-75-1. Harold Edgerton (1903–1990) Gus Solomons, 1960. Gelatin silver print, 51 × 41 cm

Fashion photographers have also staged spectacular scenes for magazines. John French, a photographer who mentored David Bailey, created his most memorable fashion pictures for The Daily Express. His 1959 image of two women’s legs caught mid-step is a monochromatic medley of black and white shoes and tights, the subtle same-sex pairing laced with lesbian readings. Bailey considered his teacher to have given him a chance because they were both outsiders, and French ‘liked a bit of heterosexual rough from the East End’.

From costume changes to directing sitters, mastering lighting and meticulous scripting, photography’s performativity holds obvious parallels with the world of theatre. These similarities are reflected in the V&A’s Theatre and Performance collection, which holds over three million photographs. This collection has a tantalizing queer beginning. It was founded in the 1920s, when the multi-talented private collector, playwright, translator and suffragette Gabrielle Enthoven donated her extensive and painstakingly catalogued holdings of playbills, designs, books, prints and photographs to the museum. Enthoven, known among her peers as the ‘theatrical encyclopaedia’, was part of ‘The Circle’, an exclusive group of the London theatre profession’s most infamous lesbians that also included Edith Craig and Cécile Sartoris. Together they would catch shows, collect memorabilia and frequent queer intellectual Soho hotspots such as The Cave of Harmony and The Orange Tree.

© Estate of Maud Sulter. All rights reserved, DACS, 2023. Maud Sulter, Clio (Portrait of Dorothea Smartt), 1989. Dye destruction print, 122 × 153 cm

[...]

For Victorian theatregoers, photography offered a novel and exciting way to take home their showtime experience. Patented in 1854, small photographic portraits known as ‘cartes de visite’ became a popular way to spread and trade images of performers, propelling many of them to celebrity status. Actors posed in costumes, recreating scenes from their shows and promoting their repertoire: one day dressed as a dapper dandy, the following a damsel in distress. Some of the most fabled showgirls, among them Vesta Tilley, Maud Allan and Loïe Fuller, utilized studio photography to boost their notoriety, toying with rumours of their promiscuous affairs with other women.

Pictures of nineteenth-century stars cross-dressing were also popular: Lulu, the stage persona of Samuel Wasgatt, poses as a female acrobat in a cinched corset and frilly shorts; club in hand, Charlotte Saunders plays a virile bearded Hercules, the sexually ambiguous homoerotic hero and lover of Abderus and Hylas. The theatre world has always had strong ties with queer communities, from staging gender play, musical mania, coded references in tongue-in-cheek scripts and cult classics like La Cage aux Folles and The Rocky Horror Show, to more recent dramas such as Lucy Skilbeck’s Joan & Bullish: Two Plays (2017) or Matthew Lopez’s The Inheritance (2019) that speak to wider themes in LGBTIQ+ life.

Words by Lydia Caston

Discover Calling the Shots now.